By RNZ.co.nz. Republished with permission.

A discharge without conviction can spare a person guilty of a crime years of struggle and stigma. RNZ can reveal Pākehā are granted more each year than any other ethnic group.

Paora Manly* was a 21-year-old law student, living off a student loan and occasional te reo Māori teaching work, when he got drunk one night at a party and hit another guy over the head with a box of Tui.

The guy had been flirting with Manly’s girlfriend. A friend egged Manly on, telling him to teach the guy a lesson. “Don’t be a pussy,” he said.

That’s when Manly picked up the nearest box of beer and ran after the guy, who had just left the party, and hit him so hard he lost his footing. The boy, his head marked with cuts from the blow, managed to get up, and run away down Wellington’s Dixon Street.

But Manly bumped into him again later that night at a brawl involving the two men’s mutual friends. Police were called and Manly was singled out because of the beer box incident earlier in the night. He was arrested on the spot.

During the car ride to the police station, Manly’s life flashed before him. He was a young, driven student, nearing the end of his degree, with strong friendships and involvement with his whānau, hapū and iwi, facing the prospect of a conviction. Through the car window, he watched strangers enjoying their Saturday night while a deep sense of regret settled in the pit of his stomach.

“I distinctly remember thinking, quite dramatically, ‘I’m going to have to change my entire life, I’m gonna have to leave Wellington, probably pick up a law degree somewhere in Auckland.’ It immediately overwhelmed me.”

Read more from Is This Justice?

Later, he apologised to the guy he had hit; told him he should never have done it. But Manly remained so ashamed, he did not tell a single member of his whānau about the assault. He went to court alone, where a duty lawyer represented him on his first appearance, and a legal aid lawyer on his second.

Neither lawyer raised the possibility of applying for a discharge without conviction, which could have spared him a criminal record. Manly said he might have been aware the option existed but he felt so ashamed, he convinced himself he would be convicted regardless of what he did.

“In those earliest stages I made my own mind up that I had no case to argue. My lawyer didn’t say anything to suggest anything different. I definitely was like, okay, I’m gonna get this charge, I’m gonna get convicted for it, so slap it on me and I’ll deal with it.”

Manly was convicted of assault with a blunt weapon. He left court relieved to leave the legal process behind, but the conviction would follow him, messing with his career and altering the course of his life.

If Manly was Pākehā, statistically he would have been far more likely to have left the courtroom without a conviction, but he is Māori.

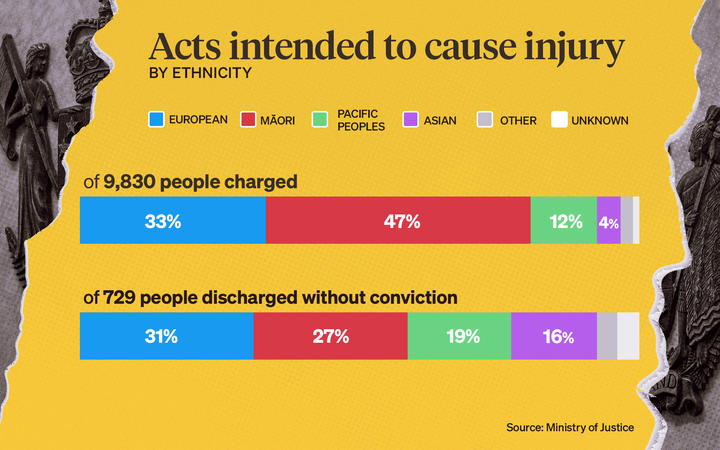

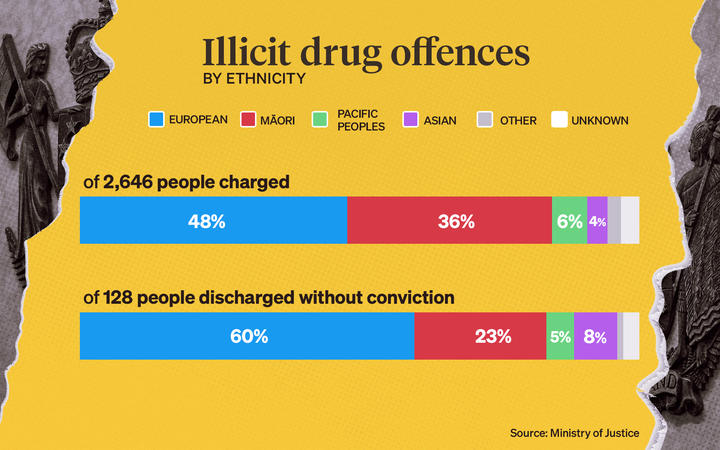

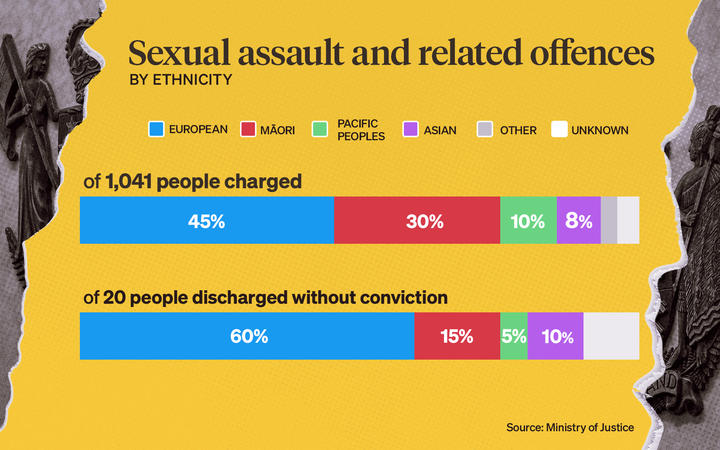

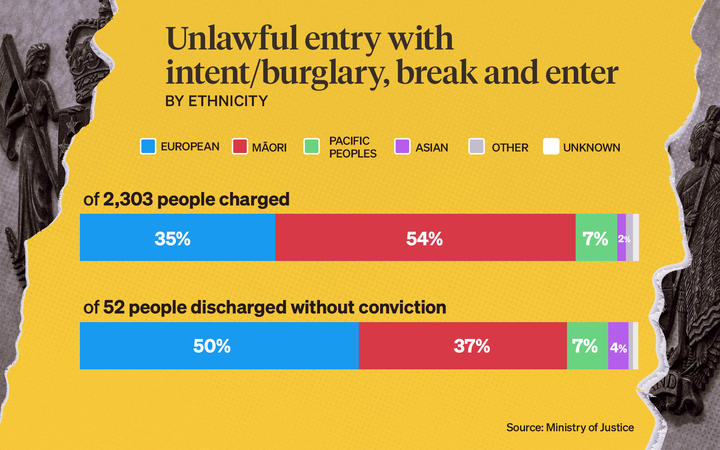

Last year, 43 percent of all criminal charges were brought against Māori, but Māori were only given 24 percent of the year’s discharges without conviction. Meanwhile, 35 percent of charges were brought against Pākehā and they received 35 percent of the discharges without conviction. Why are the figures so different?

There are three fundamental questions a judge must ask before they make a decision to grant a discharge without conviction, or what lawyers call a ‘section 106 application’: How serious is the offence? What are the direct and indirect consequences of the conviction for the individual? And are the consequences of conviction out of all proportion to the gravity of the offence?

Auckland barrister Echo Haronga, of Guardian Chambers, said an ideal section 106 applicant is someone who can clearly show how a conviction will affect their future potential. The threshold is high, so it’s not enough to say their future potential might or could be affected.

“It might be to do with their career and employment opportunities, or a promotion within their current career. It could be within education, academia, sports, and roles which required travel,” she said.

An applicant can also improve their chances by demonstrating how they will mitigate the seriousness of their offending prior to sentencing. They might do this by completing voluntary community work, repaying any financial harm, donating to a charity, giving an apology and addressing the drivers of offending through education or treatment, Haronga said.

The test appears straight forward, almost like a tick-box exercise; the more boxes a person can tick, the greater their chances of being discharged without conviction.

But Haronga said while the test is the same for everyone, people who are employed and earn a good wage are far more likely to do well. Those people, she said, are also more often than not Pākehā. That’s because, on average, Pākehā earn more income than Māori at every age, according to a 2018 study. The same study found one third of working-age Māori have no qualifications and over half have lower skilled jobs.

“A person might use affidavit evidence, or support letters from people in the community of standing who can attest to the applicant’s future potential. That’s quite difficult if you’ve exited education early, and you might not have community contacts who could support your application,” Haronga said.

“It’s also quite difficult if you’re not in the workforce at all because you don’t necessarily have the support of a prospective employer or a current employer who can attest to the difficulties you might face in your career trajectory. It’s also quite difficult if you’re simply in low-skilled work because, generally speaking, convictions are not going to preclude you from retaining or entering that sort of job.”

There’s also the question of who has the capacity and means to undertake the application process.

“They have to do a bit of arithmetic and ask, can I afford to get a lawyer to represent me on this, which may be several thousands of dollars? Can I afford the days off work to attend court? Can I afford any additional childcare? Can I afford to spend the time doing voluntary work in my spare time?”

“Generally speaking,” Haronga said, “people from large whānau have a lot of commitments, particularly around child care and caregiving for elderly relatives. They don’t necessarily have time in the evenings, where they can go and volunteer at a charity.”

Asked whether the system privileges wealthy people, Haronga said that’s a fair assessment.

Associate Professor Khylee Quince, from Auckland University of Technology’s law school, agrees. She said having quality legal representation can dramatically improve a person’s chances of obtaining a discharge without conviction. That’s because a strong application takes time.

“The most likely to be successful applications are ones where a lawyer turns up, they’ve spent quite a bit of time with the client, and they say to the client, ‘Look, you need to do something by way of an apology. You need to put together either a package of reparation, where you pay some money to a charity, or if there is an identifiable victim, you give some money to them, or you undertake a service sort of programme’,” she said.

If someone can’t afford a private lawyer, they may be eligible for legal aid, where the government helps to pay for a legal aid-approved lawyer to represent them. To qualify, a person can earn no more than $23,820 annually or $37,722 if they have a spouse or partner.

The amount of money a legal aid lawyer receives for a section 106 application can vary depending on the complexity of the case. For low-level matters, legal aid lawyers are guaranteed $200 to prepare for a sentencing hearing and an additional $250 to prepare any written section 106 application. They can apply for additional funding once the case is estimated to require work valued at 25 percent more than the fixed fee.

Quince said even if a legal aid lawyer secures $800 worth of funding, the work required to execute a strong application is worth a much greater amount than that.

“A lot of work has to go into a section 106 application. So the most successful ones are ones where lawyers are either being paid privately to put together an application for the judge or where a legal aid lawyer, out of the goodness of their own hearts, does far more than $800 worth of work.”

When people cannot afford a private lawyer, but earn too much to qualify for legal aid, they have no choice but to represent themselves.

“Māori are much more likely than non-Māori not to have a lawyer and that doesn’t stop a judge from considering an application for a discharge without conviction or for the judge to consider it without an application being made. But, to be honest, that doesn’t happen very often,” Quince said.

“Someone who is self-represented, they obviously haven’t gone away and read the Sentencing Act, they don’t know how to put that kind of advocacy application to a judge. So, therefore, you’re much less likely to get it.”

Chief Justice Helen Winkelmann accepts that many people who enter the justice system come from backgrounds of deprivation and disadvantage, which can impact their outcome.

“I think the statistics reflect, to a considerable extent, the fact that a lot of disadvantages that people carry through their lives come into the courtroom with them,” she said.

“It comes in the form of whether they have legal representation, whether they have the kind of interests that the court normally looks to protect through name suppression but also through discharge without conviction. Family connection, employment, those are the kinds of things that are commonly raised when people seek name suppression or discharge without conviction.”

She agrees the quality of a person’s legal representation also matters, and that not every lawyer will suggest the option of applying for a discharge without conviction.

“[It can depend] on whether they have a lawyer representing them, a lawyer who thinks to make an application for name suppression or discharge without conviction and how well they put their case forward.

“So there’s all that disadvantage which keeps on multiplying through the system and is carried forward and I have no doubt is reflected in those statistics.”

She said the courts are now adopting the new justice model Te Ao Marama to try to address any inequities.

“The concept of Te Ao Marama is to ensure that those people who come into our court system have the opportunity for a fair hearing, so it relies on identifying any disadvantage that they have in terms of representing themselves or being heard or understanding what’s going on in court processes.”

Quince said there’s no quick-fix to addressing these inequalities because they’re largely associated with poverty, but one thing the government could do is stop slashing legal aid budgets.

“One of the things that lawyers have seen happen over the past decade has been the shrinking of the legal aid budgets. So, obviously, it’s impossible for justice systems to address or solve poverty. But what they can do is that they can give people better access to lawyers and then to equal outcomes and justice at least.

“There’s a postcode issue here too. You get unfair access the more remote you live and again, that’s much more likely to be Māori. Good luck finding a legal aid lawyer in Ruatoria. Good luck finding a legal aid lawyer in the back blocks of Hokianga.”

Auckland barrister Quentin Duff said far too many Māori, like Manly, fall through the cracks because they do not apply for a discharge without conviction when they first enter the justice system. Many do not take the consequences seriously enough, he said, or they believe that what they have or who they are are not worth fighting for.

“The number of times people are willing to just accept convictions in order to get things over and done with and to stop appearing in court because they’re not thinking ahead to the consequences, including whether they want to travel or whether they want to go for certain jobs, [is astounding].”

The Ministry of Justice does not collect data on unsuccessful section 106 applications, so it’s impossible to know for sure whether Māori are applying less often or being turned down more frequently.

“I loathe convictions,” Duff said. “I loathe any of that for our people. And, honestly, I bite and I scratch and I kick to prevent even a single conviction, because I hate them… And yet, the number of times we get, ‘Oh, whatever, I just want to get out of here’. It’s not up to us to go, ‘Well, no, no, no, let me fight, let me fight’ because you can never guarantee a win.”

Would Manly’s outcome have been different if he had a private barrister like Duff who loathed convictions and suggested a 106 application rather than a legal aid lawyer?

“I was given her details and there was one point of contact where she said she needed to talk to me before this court date,” he said.

“Basically, the first time I actually got to talk about the whole situation was when we were at court, waiting outside.

“Now, having grown up a bit, and seeing the services a lot of my colleagues and friends provide, particularly to their Māori clients, I definitely think my lawyer probably did the bare minimum. I definitely think if I had a Māori lawyer I might have got a bit more support.”

Manly quickly realised how difficult it would be finding a job in law with a conviction hanging over him. He was required to disclose his conviction on every job application. “For a very long time, I wasn’t even getting interviewed,” he said.

In order to even get his foot in the door, Manly would call places advertising jobs before he even submitted his CV. It was almost like a pre-interview, he said. “I would contact those people and say, ‘Hey, my name is so and so, I want to be here, I want to do these things, these are my passions, but I have a criminal conviction, so let me know if there’s even a point in me applying.”

It’s these sorts of employment consequences – along with immigration limitations, travel options and even insurance eligibility – that judges must weigh when they decide whether to grant a discharge without conviction. Do the disparity in Māori and Pākeha section 106s reflect a bias?

Neither Quince or Haronga think it’s that simple.

“I certainly do not discount those experiences and I’m happy to accept that they may well have happened. But I think there’s greater issues at play here,” Haronga said.

She has successfully obtained discharges without conviction for Māori clients and if she had detected bias against other clients she would have appealed the decisions. But the issues go beyond judges, she believes.

“I think it would be wrong to lay the disparity of these data points, simply as the bias of one decision maker. Across the justice system, we know that bias, whether it’s unconscious, systemic, structural or overt, with racist motivation does contribute to disproportionately poor outcomes for Māori.

“That would include police officers making a charging decision and what kind of charge they lay, prosecutors in amending or altering charges in exchange for resolution or guilty pleas… duty lawyers and defence lawyers in providing advice to clients about the chances of achieving a section 106 could be influenced by bias.”

Quince said she would never discount bias and racism influencing decisions in the courtroom, but she believes bias plays a greater role a step before a person enters court, when a police officer makes a decision to charge a person.

“The police are the gatekeepers here. So I think the point that needs to be made is that discharges without conviction are a sentencing option that is made by a judge in court, but almost all offending is gate kept by the police.

“The disproportionality is, really, people who face charges, that’s where bias is most at play. The bias of choosing to charge one person who comes to the attention of the police versus another. The decision about two people who do a similar thing and come to the attention of the police, and the police decide to lay a charge against one and not the other. The next step is the level or the nature and level of the charge that they face.”

First time offenders may be eligible for what’s known as diversion, a scheme police operate in some circumstances when the offender agrees to a set of rehabilitation conditions. The scheme operates outside of the court process and means offenders can avoid a criminal record.

But a study by justice advocacy group JustSpeak last year found Māori who encounter police, having had no prior contact with the justice system, are twice as likely as Pākehā to be end up in a court proceeding and seven times more likely to be charged.

Younger Māori were at even greater risk of being charged, with those under 25 years old four times more likely to be charged than Pākehā.

Helen Winkelmann said while bias was not an obvious factor in the disparity, she cannot overlook the possibility that it could be.

“Judges are human, they carry the kind of prejudices that aren’t conscious, the kind of preconceptions that the rest of the population carries with them, and they have to work and strive to overcome that, and we attempt to give them the tools and the knowledge to do so.”

She said judges actively undergo unconscious bias training.

Manly’s whānau found out about his conviction by accident. The court sent a letter to his parent’s address in Palmerston North.

“It was actually my grandmother who read it. She hit me up and was like, ‘your parents don’t know about this yet do they? You better bloody explain it to them’.”

He is happy he did. He was ready to give up on his career, but his whānau encouraged him to keep going.

Not everyone is as fortunate. JustSpeak Director Tania Sawicki Mead said Māori who find themselves convicted at a young age can quickly spiral down the wrong path, their potential limited due to the consequences a conviction carries.

“What is the point of the justice system convicting you for this when it does absolutely nothing to provide a meaningful process of accountability, if that’s needed, or address the reasons why you’ve ended up in front of the court in the first place?” Mead asks.

“There’s so many people out there with convictions for low level drug offending, for example, and that conviction is the thing that holds them back for the rest of their life, not the fact that for a time in their life they struggled with drug addiction or harmful use.”

Manly has never been in trouble again and because seven years have passed since his crime, under the Clean Slate Scheme his conviction is now concealed and cannot be detected by anyone searching his criminal record. He’s happier, employed but believes the justice system needs to change.

“It’s not set up for any type of meaningful rehabilitation or reparation. It’s not actually there to fix any issues. It’s a punishment system,” he said.

“I know that for lot of people in the same situation as me, who didn’t have the whānau support that I had or who didn’t have the sort of background in education – a lot of those people would not have been able to get out of that slump in the same way that I did.”

*name has been changed

Data analysis by Farah Hancock

This article is part of the series Is This Justice? Look out for more stories next week