Nuku’alofa, Tonga—Groundbreaking research into the historical collation and translation of French Catholic records into English and Tongan has uncovered a remarkable story about how 19th-century missionaries secretly preserved rare religious texts for future generations.

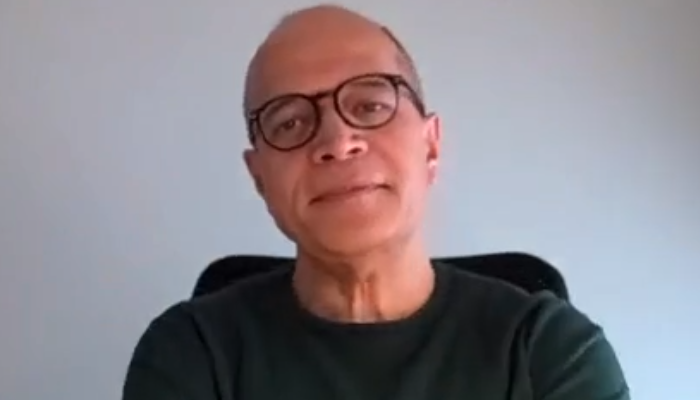

Dr Felise Tāvō, who is leading the research, revealed that in May 1980, two hidden stashes of books were discovered, one at the Catholic mission in Lifuka, Ha’apai, and another at the Fungamisi mission in Vava’u.

The books had been carefully buried in sand beneath the priests’ residences, ensuring their near-perfect preservation.

The discovery was made by Dutch historian Dr Theo Cook, who served as the Marist Archivist at the time.

Treasures of Ha’apai and Vava’u

The collections included rare theological, historical, and medical works, all in French. Among the most significant finds in Ha’apai were:

- Scripturae Sacrae Cursus Completus by Migne (28 volumes)

- Christian Perfection by Rodriguez (multi-volume sets)

- Sermons by 17th-century preacher Jacques Bossuet

- Complete works of Bourdaloue

- Books by St. Francis de Sales (incomplete set)

- Histoire de l’Église by Rohrbacher

- Les Vies des Saints by Ribadaneira

- Medical Manual from 1836 (2 volumes), etc

Tāvō speculates that the medical texts may have belonged to Fr Philippe Calinon (Patele Kalino), a missionary who also served as a self-taught doctor in Ha’apai during the 1860s.

Tāvō previously said that Fr Kalino arrived in Tonga’s Pea village in July 1844 as only the third French priest to settle at Pea after Frs. Chevron and Grange.

“He was what the French would call ‘tête dure’ (hardheaded), which was probably the kind of temperament needed for those rough and tough early days at Pea”, according to Tāvō.

He said Kalino was also a talented woodworker who was once congratulated by Taufa’ahau, King George Tupou I, on a wooden table and case that the priest made for him at Lifuka.

“But his talent that stood out the most was his knowledge of medicine, for he’s even described as “the most competent doctor in the archipelago” (Mangeret 2.265).”

Meanwhile, the Vava’u collection included:

- Life of St Teresa of Avila by the Bollandist Society (2 volumes)

- Works of St. Teresa of Avila by Marcel Bouix (3 volumes)

- Apostolic Letters of Pope Leo XIII (7 volumes)

- Le Missionnaire de la Campagne by Joseph Jouve (4 volumes)

- Exegesis of the Apocalypse by A. Chauffard (2 volumes)

- Thirty-nine other books published between 1900 and 1937, etc

A Lost Tongan Translation

One of the most intriguing discoveries is the Tongan translation of Rohrbacher’s Histoire de l’Église (History of the Church), completed by Fr Castagnier (Patele Petelo) in the 1870s while stationed in Kolovai.

According to Tāvō, excerpts of this translation were read to Chief Ata, who initially opposed Catholic presence in his estate but later attended a Catholic Katoaga de lecture.

Although the translation was published in Fribourg, Switzerland, no known copies survive today.

Where Are the Books Now?

Tāvō has received widespread praise for his exemplary work in translating and compiling the Church’s records into English and Tongan. He said these records, which have been stored in French for over a century, currently have uncertain whereabouts.

He was expected to make contact with the Catholic Church headquarters in Tonga for any leads.

Tāvō believes they may have been transferred to the diocesan archives.

Tongan-French dictionary

Tāvō also highlighted the significance of a 422-page Tongan-French dictionary, compiled and published in Paris in 1890, based on the meticulous notes of early French Catholic missionaries. The dictionary draws heavily from the records of Fr Joseph-André Chevron (Patele Sōsefo-‘Atelea Sevelo), who served in Tonga from 1842 until his death in Lapaha in 1884.

The manuscript was later reviewed and prepared for publication by Fr A. Colomb, a French Marist who signed as “P.A.C.s.m.” Colomb organised the entries and contributed an 18-page introduction on Tonga and a 22-page Tongan grammar section preceding the dictionary.

Tāvō noted that the dictionary offers a fascinating snapshot of the Tongan language as spoken in the late 1800s, capturing vocabularies used by Tongan communities and documented by missionaries. At the time of publication, the French term “Tongien” (for “Tongan”) had not yet been standardized—reflecting the era before “Tonga” (instead of “Toga”) became the official spelling and before the “ng” spelling was formally regulated in the 1940s.

Digitised for Future Generations

Tāvō said the historic dictionary is now available in the public domain, allowing scholars, linguists, and cultural enthusiasts to explore this invaluable resource.

“Even if French is an issue for you, the dictionary is interesting in that these were some of the vocabularies used by our forebears in the second half of the 19th century that were picked up by Patele Sevelo and his fellow Marist missionaries,” said Tāvō.

Those interested can access the digitised copy tinyurl.com/5n7aef6u.