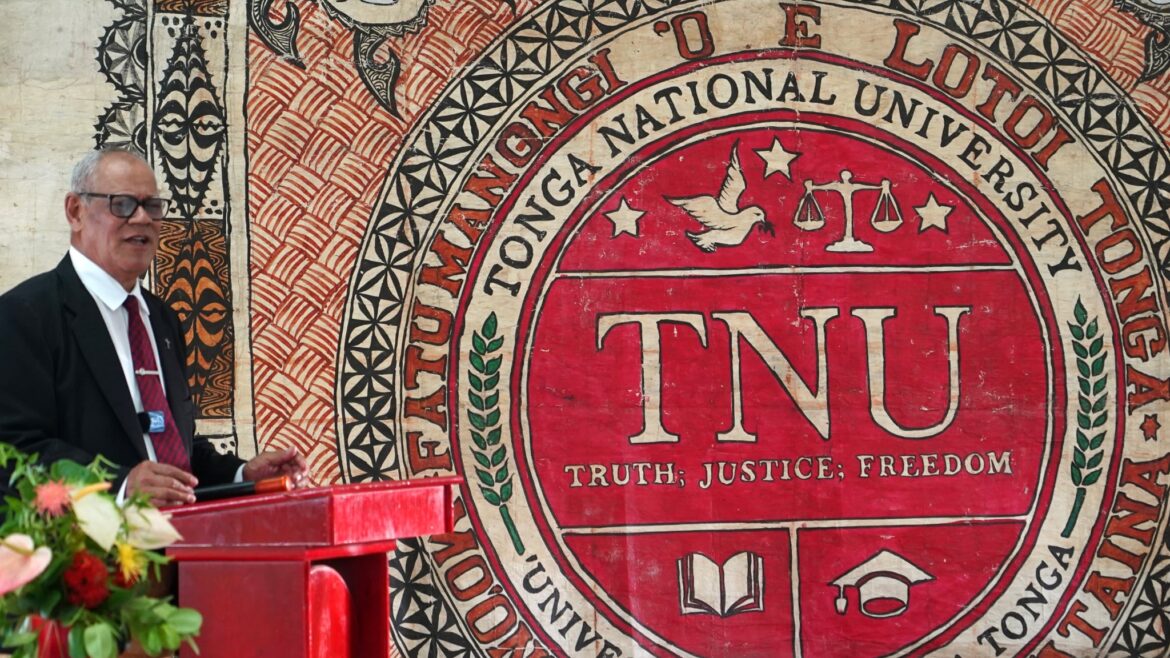

Commentary—The Tonga National University’s (TNU) move to introduce its newest degree programs in the Tongan language is both timely and justified, as the language faces threats from advancing technology and the dominance of Artificial Intelligence (AI).

The University has recently invited Tongan researcher Dr Paula Onoafe Lātū as guest speaker and spoke about Tongan studies and traditions of Tonga’s motto, God and Tonga are my inheritance.

The university stated that Dr. Lātuu’s speech would support its new language program, which is focused on the Tongan language and culture.

Saving Tongan from AI

While AI offers many benefits, it has inadvertently accelerated language erosion by making English communication effortless. Sophisticated AI tools now enable Tongans with only basic English skills to produce professional-quality writing in real time, which they can copy and send wherever needed.

This unprecedented capability has removed what was once a significant barrier, particularly for Tongans who previously struggled with English at university, often leading to academic failure.

While the TNU has yet to declare the details of its syllabus and what would be included in teaching Tongan, it is worth making a proposal.

Balancing Tongan and English

One of the critical gaps in Tongan language education is the lack of structured translation resources between Tongan and English. Translation is foundational to language learning—we see this when Palagis arrive in Tonga as workers or missionaries. Their first step is always to study Tongan vocabulary through translation, converting words between English and Tongan. Yet, there are hardly any published books or resources that systematically teach Tongan-English translation.

READ MORE: Lōkale, lisinale, kolōpale: How one leader’s Tonganisation stunt during national summit became a language revival motive

The university’s program developers should recognise that while English is essential for Tonga as the official language and a means of international communication, it is important to maintain a balanced approach between Tongan and English language studies. Instead of prioritising one language over the other, both should be equally valued in educational planning.

The other two concepts that should also be part of the syllabus are conceptualisation and contextualization. Conceptualisation refers to the process of forming ideas or concepts about something. It’s about identifying and clarifying the essential features or characteristics of a subject. For example, when we conceptualise a tree, we think about its defining attributes, like having a trunk, branches, leaves, and being a part of an ecosystem. This helps in creating a mental model or framework that aids in understanding and communicating about that subject.

Beyond Basic Definitions

Contextualization, on the other hand, involves placing a concept or idea within its broader context to give it meaning. This means considering the circumstances, environment, or background in which something exists or occurs. For instance, if we talk about a tree in the context of climate change, we might discuss its role in carbon absorption and how changing weather patterns affect its growth. Contextualization helps us see an idea’s relevance and implications beyond its basic definition.

While these examples of conceptualisation and contextualization may appear straightforward, closer analysis reveals foreign scholars’ frequent misinterpretations of Tongan cultural practices, resulting from misunderstandings of these academic processes. Similarly, these same challenges have posed the most significant barriers for our students attempting to conceptualise and contextualise English-language phenomena.

Centring Tongan Worldviews

A critical issue recently identified in contextualising and conceptualising Tongan notions and frameworks is the persistent tendency to interpret them through Anglophone cultural paradigms rather than grounding understanding in Tongan epistemological traditions

The following analysis exemplifies what the author identifies as miscontextualization stemming from the prioritisation of English conceptual frameworks over Tongan epistemology. While many scholars reductively equate nofo ‘a kāinga with Western social hierarchy systems, closer examination reveals fundamental ontological differences. Crucially, the social hierarchy model—which ranks individuals by class, power, and status, inherently generating inequality—fails to capture nofo ‘a kāinga’s defining characteristics.

Cultural Frames Before Translation

At its core, nofo ‘a kāinga derives from kinship ties rather than imposed stratification. Its structure functions through the complementary duality of ‘eiki (superiors) and tu’a (inferiors), where seniority holds paramount importance. This dynamic system is sustained by reciprocal obligation (fatongia) and sacred respect (faka’apa’apa) – manifestations of mana and tapu – rather than coercive hierarchy.

Such reciprocity becomes institutionalised through fetauhi’aki, the ongoing cultivation of relationships via cyclical exchanges of duties and respect. In contrast to Western hierarchies that concentrate resources among elites, nofo ‘a kāinga facilitates equitable distribution through these culturally embedded mechanisms of mutual responsibility.

These observations demonstrate that when teaching conceptualization and contextualization in Tongan education, instructors must prioritize the explanation and discussion of Tongan concepts within their original cultural contexts. English equivalents should only be introduced as supplementary translation aids—not as primary frameworks for understanding.

These findings argue for Tongan-centric pedagogy: teach concepts first through Tongan contexts, using English only as a translation tool. By addressing the gaps in translation resources, conceptual frameworks, and cultural contextualization, TNU’s program has the power to transform Tongan education—centering Indigenous knowledge rather than Western paradigms.