Commentary – The recent removal of lo’i hoosi pies from an Auckland bakery has exposed more than just a regulatory breach — it highlights a longstanding gap between New Zealand’s food‑safety system and the lived cultural practices of its Tongan community.

While the council acted appropriately in enforcing food‑safety rules, the situation raises a deeper question: Is it time for New Zealand to legalise and properly regulate access to horse meat for a significant segment of its multicultural population? In practice, horse meat is already circulating informally at local markets, where what appear to be unlicensed suppliers sell it as “pet food,” while members of the Tongan community purchase it for human consumption.

The result is a grey market operating without transparency, food-safety oversight, or cultural recognition—leaving both consumers and sellers exposed in ways that proper regulation could resolve.

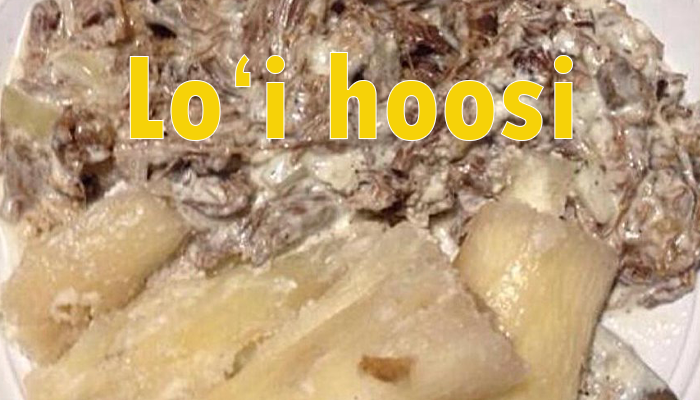

The truth is that horse meat is not new to Tongans. For generations, families in Tonga and abroad have cooked and shared lo‘i hoosi—a dish of coconut cream‑mixed shredded horse meat—making it a longstanding part of Tongan food culture. In Auckland today, it remains widely available in Tongan restaurants, church fundraisers, private family events and community gatherings.

People know where to buy it, and many have been buying it quietly for years. The demand has never disappeared — nor will it. Cultural foods are powerful markers of identity, memory and belonging.

This is where the tension arises. While it is legal to eat horse meat in New Zealand, the law requires that meat sold to the public must come from a registered, inspected processor. Yet only one facility in the entire country is licensed to supply horse meat for human consumption, which means availability is extremely limited, expensive and — in practice — inaccessible for most Tongan families.

When cultural demand is strong but legal supply is almost nonexistent, an informal and unregulated market becomes inevitable.

From a public‑health perspective, that is the real risk. Tongans are already one of the ethnic groups with the highest rates of chronic diseases in New Zealand, including diabetes, cancer, cardiovascular disease and obesity. Any food‑safety issue that increases risk, whether through contaminated meat or unhygienic supply chains, only places further pressure on a vulnerable population.

Shutting down illegal sales is not a solution on its own; what is needed is a safe and culturally appropriate alternative.

According to the 2023 Census, 97,824 people in New Zealand identified as Tongan.

While official government surveys consistently state that a high intake of saturated fat increases the risk of chronic disease—including from meats such as lamb—horse meat, as traditionally prepared by Tongans, is a lean protein.

This places horse meat in a potentially healthier category compared with fattier cuts such as lamb flaps, which contain significantly higher levels of fat and are widely sold in South Auckland, where many Tongans reside.

Kaniva News understands that although certain horse‑meat products were sold at Māngere fair markets in South Auckland under “pet food” labels, consumers continue to buy them to prepare lo‘i hoosi. This suggests it may now be time to seriously consider a regulated and transparent supply system.

The question New Zealand must now confront is this: Would regulated, authorised horse‑meat suppliers better protect public health than the current underground system, or the sale of horse meat as “pet food,” which people then buy to make lo‘i hoosi? The answer is likely yes. Proper licensing ensures:

- veterinarian screening of animals

- hygienic slaughter and processing

- temperature control

- traceability

- food‑safety enforcement

These are protections the community does not receive when it is forced to rely on a single supplier that provides limited information and may be inaccessible to many, unlike other meat suppliers that are readily available locally.

New Zealand already exports horse meat to several European countries, according to MPI, so it makes little sense that the same product is not made available through local butchers.

There is also a broader equity issue at stake. New Zealand has increasingly recognised the value of cultural food practices — from hangi to umu, from Pacific fish dishes to halal and kosher butchery. Allowing authorised suppliers for horse meat specifically for cultural demand is not about promoting the practice; it is about acknowledging reality and keeping communities safe.

The question now is whether policymakers will work with the Tongan community to bring this practice into a safe, regulated space — or whether the system will continue pushing people toward unregulated, potentially unsafe alternatives.

If New Zealand truly values Pacific wellbeing, cultural identity and public health, then the time has come for a serious conversation about legal supply pathways for lo’i hoosi. Cultural foods will not disappear, but preventable harm can — if the system is willing to adapt.